Fifteen Years on the Factory Floor: What Working Closely with Far East Manufacturers Taught Me About Quality

On average, I travelled there four or five times a year, building long‑standing relationships with factories and the people behind them. What began as a technical role focused on quality systems quickly evolved into something far more human shared learning, mutual trust, and a genuine partnership built around continual improvement.

From maintaining ISO accreditations to embedding structured quality improvement programmes, my focus has always been on building systems that work in the real world, not just on paper. Quality, in my experience, isn’t something you audit into existence it’s something you embed into every stage of order processing, manufacturing, testing, and release. Being physically present on the factory floor allowed me to work closely with teams to make that happen, ensuring processes were understood, owned, and continually refined.

During this early period, the lighting industry was in the midst of a major transformation. For decades, fluorescent lighting had dominated the global market, having first been commercially introduced and rapidly adopted by the late 1930s following the launch of the first viable lamps. Remarkably, fluorescent technology for commercial and more later on domestic applications remained a global mainstay for more than 70 years, evolving through generations but retaining the same fundamental principles well into the 2000s.

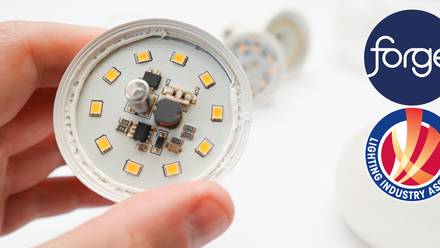

LED technology, by contrast, took a dramatically different path. It is recognised that Professor Shuji Nakamura invented white light LEDs, it wasn’t until this breakthrough in 1993 and rapid advancements in the early 2000s that LEDs became viable for general illumination, paving the way for widespread market adoption in the decade that followed. By the time I began travelling to the Far East, LEDs were still relatively new with their performance improving at a rapid pace, and with that the supply chain adjusting to the demands of more complex optical, thermal, and electronic requirements just as quickly.

What I’ve witnessed since then has been extraordinary. Far East manufacturers didn’t just adapt to the LED revolution, they accelerated it. Facilities invested heavily in automation, precision manufacturing, advanced testing systems, and high‑skilled engineering capability. The speed at which they moved from producing relatively simple fluorescent fittings to highly complex, driver‑integrated, thermally‑engineered LED luminaires was unlike anything the industry had seen before.

Their commitment to growth, technology adoption, and manufacturing excellence has directly pushed the lighting industry forward to higher efficiency products that the market needed to offset the ever-rising cost of energy as well as reducing environmental impact. The contrast with the slow, steady arc of fluorescent development highlights just how quickly, and effectively the Far East embraced LED technology, delivering these saving to the mass market.

In the early days, technical expertise alone wasn’t enough. Working effectively in the Far East meant understanding the culture, customs, and rhythms of local business life. But as with all good business activities relationships come first. Trust isn’t assumed, it’s earned through consistency, patience, and showing up.

Meetings didn’t always start with KPIs or corrective action plans; they often began with green tea, conversation, and genuine curiosity about one another’s objectives. Once I learned to slow down, listen, and adapt my approach, progress for both parties accelerated. Quality conversations became collaborative rather than directive, and solutions were developed together rather than imposed.

And then, of course, there was the food. Early on, I discovered that “something light for lunch” doesn’t translate the same way it does back in the UK. When a dish arrives sizzling, colourful, and occasionally still moving, you quickly realise you’re a long way from a ham sandwich and a packet of crisps. But those shared meals, whatever was on the plate, often became the foundations of real trust and partnership.

Travelling to the Far East so frequently inevitably comes with challenges. Being 6,000 miles away from family, managing long time zones, and spending weeks at a time overseas tests your stamina as much as your professionalism. There were moments, standing in a factory at the end of a very long day when the distance felt very real. But those sacrifices also brought perspective. Being physically present on site is incredibly powerful. You see issues early, discuss them as they unfold, and solve them at source. Quality improves when you are close to the process and close to the people responsible for it.

Working with Far East manufacturing partners teaches you very quickly that quality is only one part of a much bigger picture. As a design partner, you’re constantly navigating a chain of dependencies that stretch across oceans and continents. Long shipping ties, changing freight markets, and the sheer scale of production volumes all shape the context in which quality decisions are made. A perfectly manufactured product can still become a problem if it sits in a port for weeks, misses a seasonal window, or arrives damaged because the logistics link in the chain wasn’t as strong as the manufacturing one.

It’s in these moments you realise that managing quality at distance is not simply about achieving specification, it’s about thinking ahead, anticipating failure points, and understanding that small decisions made in a factory office can have huge consequences thousands of miles away. When lead times stretch into months, every corrective action, every ECN/ECR, every packaging tweak, every shift in demand carries weight.

True quality management in the Far East demands a broader lens. It requires an appreciation for the entire journey a product takes, the pressure points it will encounter, and the commercial risks attached to every stage. It reminds you that quality doesn’t end at the factory door, in many ways, that’s where the most unpredictable part of the story begins.

One of the most rewarding aspects of working with Far East manufacturers has been their openness to learning and improvement. When presented in the right way, teams were highly receptive to new ideas, structured problem‑solving, and data‑driven decision making. Continuous improvement is no longer seen as criticism, it is embraced as progress. That willingness to learn, adapt, and grow has been a driving force behind every improvement made over the years. But learning alone isn’t enough. The real strength comes when learning is paired with trust.

Regular travel allowed relationships to mature naturally. Familiar faces became trusted partners. Conversations became more open, issues are raised earlier, and accountability is shared rather than assigned. Quality stops being a department and became a culture, owned collectively by people who know one another well enough to be honest, even when the truth was uncomfortable.

This blend of learning and trust creates something incredibly powerful: a business relationship that’s resilient, transparent, and capable of long‑term improvement. When teams trust each other, they share problems before they become crises. When they learn together, they evolve together, raising the bar with every project. It’s here, at the intersection of capability and relationship, where strong businesses are forged.

Implementing the right controls and processes is ultimately what safeguards PO‑to‑PO consistency. It’s not enough for a factory to produce one good batch, true quality lies in repeatability. This means working together, building robust systems that ensure every purchase order follows the same disciplined path, controlled material sourcing, stable production parameters, validated testing regimes, and clear communication loops that catch issues early. Over time, this creates a predictable and controllable rhythm the product that arrives today looks, performs, and lasts exactly like the one delivered a year earlier. And when that level of consistency becomes the norm, it does more than protect supply, it strengthens the brand itself. Customers begin to associate reliability, performance, and trust with your name, and that perception becomes one of the most valuable assets any business can earn.

Looking back, my years working with manufacturing partners in the Far East have profoundly shaped how I view quality and leadership. They reinforced the belief that the best results come from collaboration, cultural understanding, and being willing to learn as much as you teach.

Quality improves when you’re close to the process, invested in the people, and committed to the journey.